Blog by Sumana Harihareswara, Changeset founder

Testing, Testing

Hi, reader. I wrote this in 2019 and it's now more than five years old. So it may be very out of date; the world, and I, have changed a lot since I wrote it! I'm keeping this up for historical archive purposes, but the me of today may 100% disagree with what I said then. I rarely edit posts after publishing them, but if I do, I usually leave a note in italics to mark the edit and the reason. If this post is particularly offensive or breaches someone's privacy, please contact me.

When I was in high school, a zillion years ago, I got reallllly good scores on the SAT I* and the PSAT (which played the Silver Surfer to the SAT's Galactus). I was good at taking standardized tests. I was the kind of completionist perfectionist who was disappointed at getting, like, a 1570 out of 1600 when I took the SAT. I believe it was Mateo who told me**: the upper reaches of SAT scores, between about 1450 and 1600, are essentially a matter of luck, volatile variation that it's practically impossible for the test-taker to control.

When I was in high school, a zillion years ago, I got reallllly good scores on the SAT I* and the PSAT (which played the Silver Surfer to the SAT's Galactus). I was good at taking standardized tests. I was the kind of completionist perfectionist who was disappointed at getting, like, a 1570 out of 1600 when I took the SAT. I believe it was Mateo who told me**: the upper reaches of SAT scores, between about 1450 and 1600, are essentially a matter of luck, volatile variation that it's practically impossible for the test-taker to control.

I was catching up with an old colleague last month and mentioned that I've been thinking a lot, in the last few years, about assessments, about how we assess our own and each other's skill and knowledge. And he was curious about what's prompted that. I talked a bit about how we form ambition -- to learn something and to have that mastery validated by people whose judgment we trust -- and how we don't have good ways to check our own skill levels in programming, so the job market ends up fulfilling that role (badly). And about summative and formative assessment, and how it can be hard to really make a space for truly formative assessment. And I didn't get around to talking about the function of public awards in these systems but that's connected too. And we got to talking about performance evaluation cycles at workplaces, and how working with superlative colleagues can mean always feeling behind.

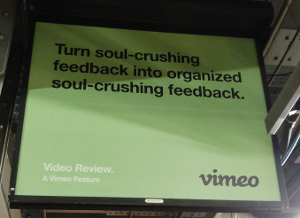

And I meant to joke about Quantified Self-Loathing, about how it's now easier than it's ever been to constantly compare your own work to that of the best people in your field. Lyndsey once joked with me: "'Oh look, this person made 36% more commits than you did last month.' The problem isn't Quantified Self, it's Quantified Other People's Selves."

And I meant to joke about Quantified Self-Loathing, about how it's now easier than it's ever been to constantly compare your own work to that of the best people in your field. Lyndsey once joked with me: "'Oh look, this person made 36% more commits than you did last month.' The problem isn't Quantified Self, it's Quantified Other People's Selves."

But -- I realize, looking back -- of course I want to dig into how we test. Because the particular kind of scaling-up of human interaction our civilization has chosen demands constant pseudo-objective assessments: star ratings, application processes, credit scores, engagement metrics. Precarity and austerity and the gig economy factor in; one's not told that one could not possibly get what one wants, but that one failed a test that others passed. And panopticon-style surveillance adds the layer of other unaccountable assessors, whose criteria and even whose identities are opaque. And, by living my ordinarily life, I am complicit in becoming endless statistics; my own actions get added to this soup and used to judge others.

To be at home, to be at ease, is to be in a place where -- ideally -- no one is assessing you, judging you. Second-best is to be in a place where they're judging you, but fairly, by rules you know and can follow.

To be at home, to be at ease, is to be in a place where -- ideally -- no one is assessing you, judging you. Second-best is to be in a place where they're judging you, but fairly, by rules you know and can follow.

The word I haven't used yet here is "anxiety".

I visited the Bay Area late last year and caught up with some old friends. It turns out a few of them are rich now. I mean, not "my escape plan for the coming climate refugee crisis involves an island" rich as far as I know, but "worked at the right place at the right time and acquired the right stocks" rich. And then there are some folks, just as talented, who did not. There's a reason they call it "winning the startup lottery."

I only bought a few tickets to the startup lottery, and I did not win, and I stopped playing. Financially I am better off than a LOT of people. But I feel that same multidimensional vertigo that probably a lot of my readers feel:

- class mobility disorientation stemming from the dissonance between childhood and now

- class consciousness stemming from the delta in financial stability between me, now, and most of the people I pass on the sidewalk every day

- class consciousness stemming from the delta in financial security between me, now, and the rich people I run into via work and my social circles

- existential uncertainty about the future of all of humanity, making all "investing for the long term" financial decisions suspect***

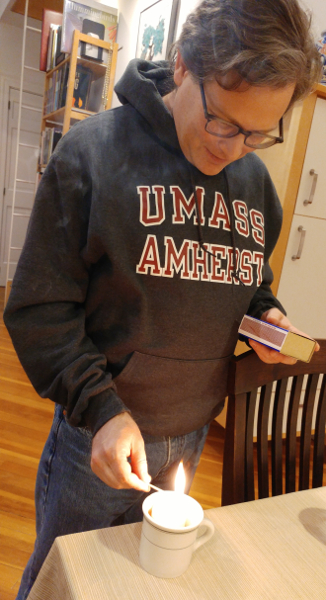

The disorientation of travel can actually be a relief sometimes, when it matches an inner antsiness. This past weekend Leonard and I went on a tiny vacation to see a few friends -- Mike in Cleveland, then the Zack-and-Pam household in Pittsburgh. We've known Zack Weinberg (now Doctor Zachary Weinberg!) for ages, starting back when we all lived in the Bay Area. Sunday afternoon it was super cold out, so we got out Zack's candlemaking supplies and I learned a bit about how the whole process works -- I'd seen the implements and read his candlemaking tribulation blog posts back in the early 2000s but this was the first time I'd helped with the whole process, start to finish.

The disorientation of travel can actually be a relief sometimes, when it matches an inner antsiness. This past weekend Leonard and I went on a tiny vacation to see a few friends -- Mike in Cleveland, then the Zack-and-Pam household in Pittsburgh. We've known Zack Weinberg (now Doctor Zachary Weinberg!) for ages, starting back when we all lived in the Bay Area. Sunday afternoon it was super cold out, so we got out Zack's candlemaking supplies and I learned a bit about how the whole process works -- I'd seen the implements and read his candlemaking tribulation blog posts back in the early 2000s but this was the first time I'd helped with the whole process, start to finish.

Zack showed me how to measure and cut wicks, thread them into the molds, and secure them. The bit that seems like the top at first, where you pour the wax, ends up being the bottom of the finished candle. We melted a block of whitish/clear paraffin in a bain Marie. We had bits of dye we could put in -- red, yellow, green, and blue, I think. What color did we want to make? Orange, I suggested. So we put in bits of yellow and red dye. The hot, molten wax is translucent, practically transparent; to test the color you have to spoon a bit out and drip it onto a surface, and let it cool. And then, to replicate a bit of the thickness of a real candle, you drip a bit more on and let it cool, so the light has to refract through more of the solid wax. The pinkish hue was fine for a pretty sunset or a dessert, but it wasn't quite the orange we wanted, so we added more yellow, and more, and saw the test drips iterate through shades of salmon. OK, we figured, orangey orange wasn't going to happen, we'd have some nice rosy candles.

Two of the three molds leaked and leaked and leaked -- the hole for the wick loves to let hot wax out, especially when a first-timer like me pours the wax in a bunch of stutters instead of one fluid motion. Repour, watch, see a leak, pour/scrape the wax back into the pot, repeat. It turned out we didn't quite have enough wax for the three forms, so we stirred in a few handfuls of crumbled uncolored soy wax. Finally we made an icewater bath in a tray and set the tray of cooling molds in there, which slowed the leaks down so the wax had time to harden before it could escape.

And then when we slid the cooled candles out of their molds -- orange after all! You have to wait to find out what you'll get.

And then when we slid the cooled candles out of their molds -- orange after all! You have to wait to find out what you'll get.

We briefly lit the small one, the one Pam and Zack gave Leonard and me to take with us. We joked that we were obeying the "Plea from the Author" of the candlemaking book Zack had on his shelf, which I'd skimmed during the melting-waits and cooling-waits. In The Candlemaker's Companion: A complete guide to rolling, pouring, dipping, and decorating your own candles, Betty Oppenheimer writes:

Please, please, please, burn candles! Too many people save them, look at them, fondle them, keep them wrapped up in a drawer or forever in the same centerpiece holder, never to be burned.It breaks my heart....

On a practical level, you will need to burn your candles to test the compatibility of your wax and wick. The more you burn, the less painful it will be to see your work go up in flames, and the more you will appreciate the fruits of your labor....

...Lead by example, and burn your work!

We lit the candle to test it, to check the ratio of the molten wax pool to the diameter of the pillar, but also just because a candle is meant to be inflamed. And because it's a rich warm quiet moment, to silently watch the flame on a candle you made with friends you've known since before you were quite you.

* "However, in 1997, the College Board announced that the SAT could not properly be called the Scholastic Assessment Test, and that the letters SAT did not stand for anything." Whenever I hear about an initialism giving up the words it used to be based on I remember that old saying: if you don't stand for anything you'll fall for everything!

** In the editing room in IA7, probably, loading edited stories onto the big Mac to flow into Quark XPress. He and I co-edited the high school paper's opinion page together and talked about X-Files. Now we're both in the tech industry and we're both Recurse Center alumni. I still marvel that we ran into each other again.

*** And of course that last one is on a whole other level. Everything else, I at least theoretically know how to deal with: meditation, activism, keeping a varied friend group, and so on. Climate change grief -- "This civilisation is finished: So what is to be done?" -- pervades, and "Its severity and urgency and the sheer evil of how we are sliding into it demand that we tear our lives up to try to stop or at least slow it down." And I am a coward about this, and this footnote is part of me trying to talk about it so I become a bit less of a coward.