Blog by Sumana Harihareswara, Changeset founder

What You Miss By Only Checking GitHub

Too many researchers, entrepreneurs, marketers, open source sustainability activists, and commentators assume that activity on GitHub and data from the GitHub API is a reasonable proxy for activity in and data about open source as a whole. It is not.

Further: if you're a funder, and you limit your recipients to projects that live on GitHub, you're leaving out quite a lot of the infrastructure you probably want to fund.

GitHub's a big, easy-to-search resource with an API, so it's an appealing place to start. But pursuing open source sustainability/security/data only through projects on GitHub is an example of the lamppost fallacy. The story goes that a drunk guy says, "I dropped my keys, will you help me look for them?" "OK, sure. Where'd you drop them?" "Under that tree." "So why are you looking for them under this lamppost?" "Well, the light is better here."

I notice this phenomenon at least a few times a quarter.

Supply chain security

For instance, last year, GitHub itself made my eyebrows go up with one of the graphics in their marketing material for GitHub's supply chain security features, brought to my attention by Ned Batchelder.

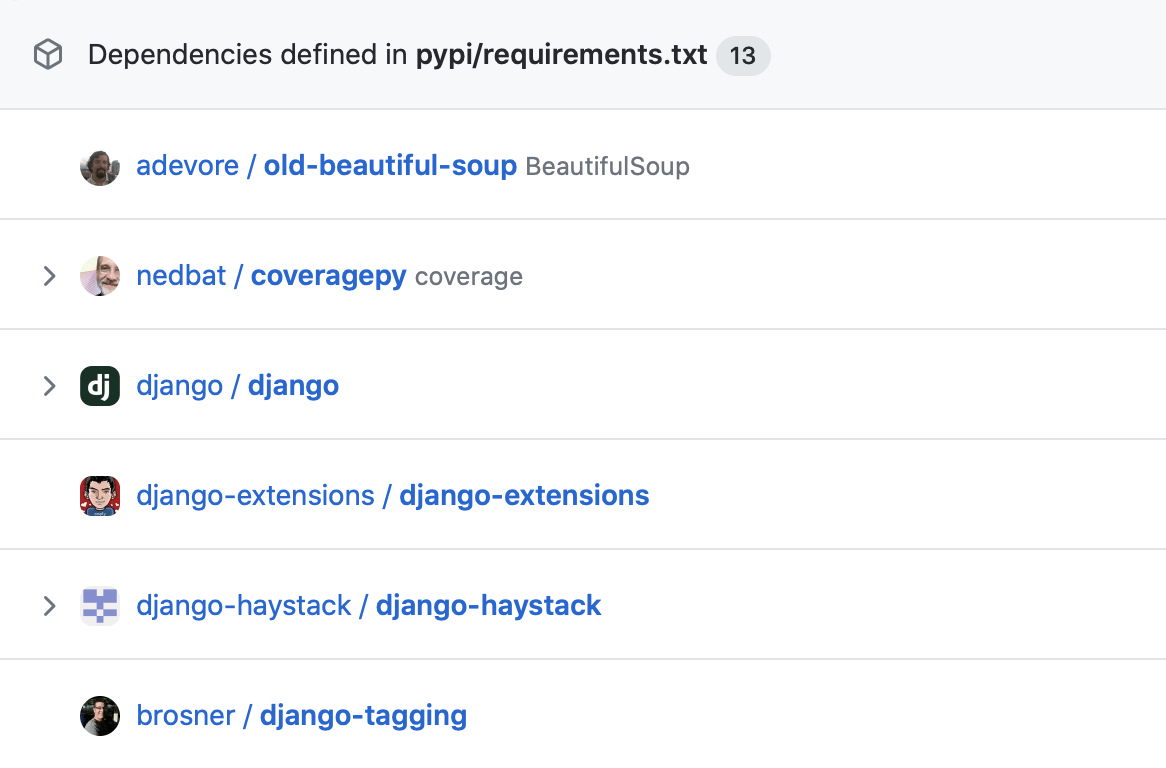

Dependencies defined in pypi/requirements.txt: adevore/old-beautiful-soup (BeautifulSoup), nedbat/coveragepy (coverage), django/django, django-extensions/django-extensions, django-haystack/django-haystack, and brosner/django-tagging. GitHub security overview

GitHub's graphic lists a few GitHub repositories associated with "dependencies defined in pypi/requirements.txt" for a sample project. It especially caught my eye because it starts with a repo for the popular Beautiful Soup screen-scraping library. My spouse Leonard Richardson created and maintains Beautiful Soup.

But the repo in the graphic is wrong. It isn't Leonard's. Because Leonard doesn't develop Beautiful Soup on GitHub. (He uses the Launchpad forge.)

Python-specific details you can skip:

Now, arequirements.txtfile that (we infer) is reading from the public Python Package Index (PyPI) is going to list the PyPI project names of those packages. Here is an examplerequirements.txtfile:

asyncpg>=0.26.0

Jinja2>=3.1.2

uvicorn>=0.18.2

starlite>=1.7.1

gunicorn>=20.1.0

uvloop>=0.16.0

Note the absence of URLs, or GitHub-namespaced repository identifiers. Thisrequirements.txtfile does not specify where the source code for those packages is hosted; it's asking for a set of packages hosted on PyPI. Maintainers can upload packages to PyPI from their own computers, or from automated actions on platforms like GitHub and GitLab, etc. Someone could poke around with the APIs and analyze the "urls" field(s) associated with particular uploads, but there's no rule saying maintainers have to fill that in. Neitherrequirements.txtfiles nor any PyPI APIs can even confirm whether development is anywhere public at all, much less on a particular platform and at a specific URL.

Yet GitHub's marketing material is implying that, for each PyPI-hosted dependency in that file, it'll tell you which GitHub repository is where that project is maintained.

And most of the dependencies in that graphic are the official project repositories, such as Ned's Coverage.py. But not Beautiful Soup! No, "Beautiful Soup" shows up as "adevore/old-beautiful-soup" which is Aaron DeVore's unofficial fork of Beautiful Soup from 2009. As far as I can tell, he did not package it up and upload to PyPI, so there's no direct link between the official Beautiful Soup package on PyPI, or any Beautiful Soup-related package on PyPI, and Aaron's GitHub repository. So there's no PyPI project you could list in pypi/requirements.txt that would get you Aaron's fork! How did they make that leap?! And why?

If you're looking to manage the security of your dependencies by relying on GitHub, and one of your dependencies is the official Beautiful Soup package on PyPI, then GitHub translating that into "oh you must mean Aaron's not-on-PyPI fork that was last updated 13 years ago!" is ... not going to be helpful to you.

Funding

Last week, StackAid crossed my radar. StackAid, which is now in beta, looks to be a bit like Tidelift -- a "pay the maintainers for software you use" platform -- but with differences in pricing, the subscriber market, and what subscribers get in return. StackAid is only a mechanism for donation, unlike Tidelift which then provides subscribers with a bunch of benefits such as commercial-grade maintenance guarantees regarding security and licensing, customer support from Tidelift with a Service Level Agreement, etc. (Disclaimer: I do some consulting for Tidelift.) Tidelift is more enterprise-focused, with starter pricing at USD $30,000 per year for teams of up to 50 developers, and has "Schedule a Demo" as the first step for potential subscribers. StackAid is probably an easier way for individuals and 5-person companies to support projects they depend on, and has lower minimum pricing and what looks like a more self-managed signup flow. (Right now StackAid is limited to the NPM ecology but they're working on expanding beyond that.)

I mentioned StackAid to Leonard. He took a look and realized that currently he would not be able to claim money through StackAid because it assumes fundable projects are on GitHub: "Owners of open source projects can claim their repositories by installing the StackAid GitHub app." Beautiful Soup can receive income from Tidelift because Tidelift is working from package dependencies/identities from package managers/repositories such as PyPI, RubyGems, Maven, etc. rather than just GitHub.

But! StackAid says it's working on GitLab access for supporters; certainly expanding beyond GitHub will help and I'm glad they're aware of the issue, and I figure there's a possibility they'll expand to integrate with Launchpad, or offer some alternate attestation mechanism, so Beautiful Soup and projects like it can claim income. And I understand that, when you're launching the first, beta iteration of an NPM-focused platform, you gotta offer that common-use-case flow first, and GitHub is that.

Research and infrastructure support

The place I saw this GitHub-only perspective that really gave me pause was in Working in Public: The Making and Maintenance of Open Source Software by Nadia Eghbal, 0578675862, published by Stripe Press, 2020. (I still have a longer review of Working in Public brewing.) In her analysis, Eghbal chooses to ignore all projects that don't use GitHub (p. 21).

I picked up Working in Public because I care about open source as infrastructure and how we sustain it. But if you exclude development work on forges and platforms other than GitHub, then you are excluding quite a lot of active, widely-used open source projects, such as -- you know, at this point, instead of just citing Beautiful Soup as an example, I'll list about two dozen:

- the Linux kernel (processes patches on a mailing list)

- Debian (uses salsa, a self-hosted GitLab)

- OpenStack (uses Gitea and Gerrit hosted on OpenDev)

- Ubuntu, Inkscape, and Beautiful Soup (use Launchpad)

- Arch Linux (uses a self-hosted GitLab)

- Apache (uses self-hosted Subversion and Bugzilla)

- autotools, including autoconf (uses Savannah)

- gcc (processes patches on a mailing list and uses self-hosted Bugzilla and a self-hosted git repo, browseable via the gitweb interface that comes with git)

- GNU C library or gnulibc (processes patches on a mailing list and uses Sourceware.org Bugzilla and git)

- freedesktop.org which includes Wayland, a bunch of important window systems, command line utilities, etc. (uses a GitLab instance)

- OpenBSD (uses self-hosted CVS and receives bug reports on a mailing list)

- FreeBSD (self-hosts git using cgit and processes bugs on self-hosted Bugzilla and Phabricator)

- Docutils (uses Sourceforge)

- BIND (uses the Internet Systems Consortium's GitLab instance)

- KeePass (uses Sourceforge)

- GNOME (uses a GitLab instance)

- KDE (uses Phabricator and a GitLab instance)

- MediaWiki (self-hosts Gerrit for code review and Phabricator for issue tracking)

- LibreOffice (self-hosts Gerrit and Bugzilla)

- Blender (self-hosts Phabricator)

- Eclipse IDE (self-hosts using Bugzilla and gitweb)

- OpenEmbedded (self-hosts using cgit) and Yocto Project (also self-hosts a cgit instance) -- thanks Joshua Lock for these pointers

- Rocky Linux, the successor to CentOS (self-hosts using Gitea and GitLab)

- Gentoo Linux (self-hosts using gitweb and Bugzilla)

- emacs (uses Savannah)

If your analysis doesn't cover any of these, then you aren't going to be able to speak to the sustainability concerns they have, which are likely structurally and qualitatively different from those of the median project on GitHub. Of course some of the difference is in age; legacy and infrastructure projects (often with long-lived codebases) likely have different onboarding, testing, copyright/licensing, and funding difficulties than do newer ones. For further differences, check out "The penumbra of open source: projects outside of centralized platforms are longer maintained, more academic and more collaborative" by Milo Z. Trujillo, Laurent Hébert-Dufresne, and James P. Bagrow: EPJ Data Sci. 11, 31 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-022-00345-7 :

.... In many ways, however, GitHub is a convenience sample. We need to assess its representativeness, particularly how GitHub's design may alter the working patterns of its users. Here we develop a novel, extensive sample of public open source project repositories outside of centralized platforms like GitHub. We characterized these projects along a number of dimensions, and compare to a time-matched sample of corresponding GitHub projects. Compared to GitHub, these projects tend to have more collaborators, are maintained for longer periods, and tend to be more focused on academic and scientific problems.....

We find that the Penumbra emphasizes academic languages (TeX) and older languages (C, C++, PHP, Python), while GitHub represents more web development (JavaScript, TypeScript, Ruby), and mobile app development (Swift, Kotlin, Java)....

Importantly, projects in the Penumbra also appear to be more heterogeneous in important ways. Namely, we find more skewed distributions of files per repository and average number of editors per file, as well as more bursty patterns of editing. These bursty patterns are characterized by a skewed distribution of interevent time; meaning, projects in the Penumbra are more likely to feature long periods without edits before periods of rapid editing....

The picture of open source dynamics being drawn here is significantly different from the picture Eghbal draws (maintainers are celebrities who are "known for who they are, rather than which projects they're involved in" (pp. 36-37)). If you want to understand -- and fund -- open source infrastructure and the maintainers who keep it going, a GitHub-only analysis will be significantly misleading.

How to reach beyond GitHub

I acknowledge the same thing that the authors of "The penumbra of open source" do: it's super attractive to grab the analysis-ready data GitHub provides. "The Penumbra hosts explored here are fundamentally harder to sample and analyze." But we do have some tools and resources to reach into the richer and more heterogeneous world.

The "penumbra" researchers in their paper suggest some alternative methods, and mention Software Heritage as well. Check out the Software Heritage archive to browse a lot of open source software that isn't hosted on GitHub. The Community Health Analytics Open Source Software (CHAOSS) folks also offer software to help you fetch and analyze history and collaboration artifacts from several tools and platforms; GrimoireLab helps gather information from lots of sources instead of just the GitHub API.

And even when you're just following the news, when you come across some new headline or initiative or statistic about open source, it's worth checking: do they only mean "on GitHub"? Kind of like when I see a headline about "everybody" and they mean "in the US". Some critical thinking will help you correct for the skew introduced by this all-too-common assumption.

Comments

Sumana Harihareswara

https://harihareswara.net

20 Sep 2022, 16:34 p.m.

Sumana Harihareswara

https://harihareswara.net

20 Sep 2022, 17:02 p.m.

It was out of scope for this post to cover reasons why open source projects might prefer to use a self-hosted forge or a vendor other than GitHub. But for some of my thoughts on the different use cases, participation structures, etc. that get easier when we have more forge choices, check out the scenarios and discussion in my piece from last year, "What Would Open Source Look Like If It Were Healthy?"

Some "AND ANOTHER THING" thoughts:

Even if a project is on GitHub, "how many contributors does this open source project have?" or "how much contribution is this project getting?" are not simple questions that you can always answer using the GitHub API, partly because as ACROSS has observed, the built-in GitHub stats aren't as great at capturing "contributions like outreach, finance, infrastructure, and community management... [and] work like idea generation or bug finding", and partly because "even for projects that DO use GitHub, you still miss lots of context if you ONLY follow there. Eg Django and Python both have the most meaningful design decision discussions elsewhere (forums, mailing lists) even with the source code on GitHub." (-Jacob Kaplan-Moss)

Also check out a talk I gave on pitfalls in open source metrics in 2016.

Conversation sparked by this post in the Fediverse has included some discussion of discoverability, which is a factor that frequently comes up when we discuss decentralization on the web. I don't frequently use OpenHub but that could be another index to use. I'd welcome pointers to indices other than Software Heritage and OpenHub that provide discoverability of open source projects across heterogeneous platforms.

This reminds me of another audience that might only think to check GitHub: new contributors who are looking for their first opportunities in open source. At Open Source Bridge 2013, Fiona Tay presented "My First Year of Pull Requests" to share her perspective as a new contributor; I remember that the more seasoned FLOSS participants in the room found it striking that THE way she had looked for projects to join was to search GitHub. But my focus in this post is on people and institutions with more power, resources, and savvy, who are setting up platforms or promulgating conclusions that will affect many.